by Daniel K. Statnekov |

| ©1998 - 2006 Daniel K. Statnekov |

|

By the end of 1911, board track speeds had noticeably spiraled upward due

to refinements in engine technology and track design. Whereas the

first tracks, following the practice of the earlier bicycle tracks, had

been moderately banked at 25 degrees in the corners, banking on the motordromes

was repeatedly increased until 60 degrees became the norm.

This had the immediate effect of producing higher speeds, and a less obvious but sinister aspect of track safety, as riders were now becoming intimately familiar with the phenomenon of "G" forces. Spectators looked down onto the track from bleachers at the top of the boards; consequently, a loss of traction in the steeply banked turns was exceedingly dangerous to both rider and spectator alike. At any time in the midst of a race, centrifugal force could send a rider and his machine over the top of the track and into the crowd.

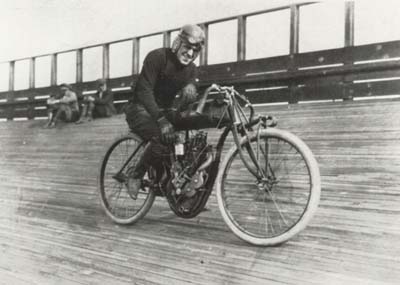

By 1912, Jake DeRosier was a veteran of over 900 motorcycle races.

Although constantly exposed to ever-increasing speeds, Jake had avoided

serious injury by dint of his good luck and excellent riding skill.

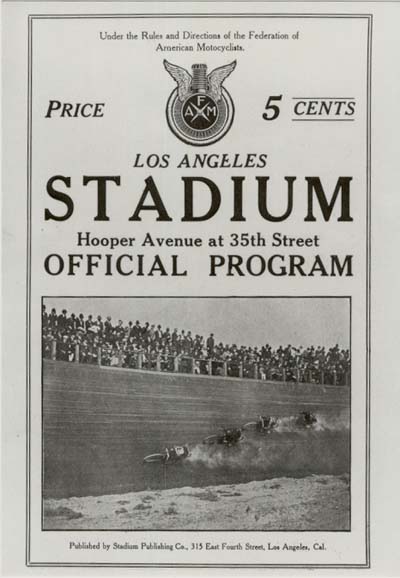

In February, the Excelsior star accompanied several members of the Chicago

team to California for the opening of a new 1/3-mile stadium motordrome in

Los Angeles. One of DeRosier's teammates was Charles Balke.

Originally from California, Balke's unyielding style had earned him the nickname of "The Fearless One" or "Fearless" Balke. From the very beginning, the two men took a dislike to each other. The management of the L.A. motordrome, seeing the crowd appeal of their rivalry, staged match races between the two teammates on identical Excelsior racers. On March 12th, in their final event, the two rivals rode elbow to elbow as they lapped the boards, neither rider giving an inch.

Balke was riding near the baseboards when his pedal touched the track surface. Instantly, he lost control and his machine shot up the track hitting DeRosier's bike and bringing him down. The "Fearless One" was lucky and fell clear of the tangled machines, sustaining only minor injuries. DeRosier suffered far worse and was picked up unconscious from the baseboards with a thigh broken in three places. The injured rider was rushed to the hospital for an operation that nearly proved fatal. After several months of improvement the former Indian star suddenly took a turn for the worse and underwent another surgery. Again his life was in danger and it was decided to move him home to Massachusetts, his mother and young wife traveling with him. In February of 1913, DeRosier entered the hospital in Springfield for a third operation. Afterwards he appeared well, but shortly thereafter his family was summoned and he died on the evening of February 25th. Hundreds attended his funeral and work at the Indian factory ceased while the funeral procession passed by. On the same day that DeRosier was buried, Oscar Hedstrom's retirement became effective. Although various theories have been proposed to explain Hedstrom's sudden departure from Indian, no one ever discovered the specific reason for the 42 year-old chief engineer's retirement which came as a surprise to most of the factory personnel. As the inventive genius behind Indian's success, Hedstrom's departure was a serious blow to Indian's long-term racing prospects. Ironically, Charles "Fearless" Balke switched from Excelsior to Indian and became the standout Indian rider of 1913, winning important road races, board track, and dirt track events for DeRosier's former employer.

Besides the accident that claimed Jake DeRosier's life, another significant

racing tragedy took place in 1912. Beginning in 1911, a young rider

from Texas, Eddie Hasha, began to make his mark on one of the Hedstrom-designed

Indian 8-valves. Hasha was very fast, and in May, at the Playa del Rey,

California resort motordrome, he set a new record for the mile, attaining a

speed of 95 mph.

Dropping one hand, he adjusted something and at once picked up enough speed to close on the single rider who had slipped past him. The next instant Hasha shot up the track at a sharp angle and struck the rail. He rode the railing for about a hundred feet, crushing out the lives of four boys who had been watching the race with their heads stuck out and injuring about ten others. The machine continued along the rail until it struck a large post, which threw Hasha to his death in the grandstand. After hitting the post, the riderless machine tore along the railing for a few more feet and then dropped down on the track in the path of another rider, Johnny Albright. The wrecked machine struck the Denver rider in the shoulder and Albright went down with terrific force. Then, mixed up with two machines, he slid along the track for about 240 feet. Albright was unconscious when picked up and five hours later died in the hospital without regaining consciousness. It was one of the few cases in the history of the New York Times that motorcycling was front page news. Subsequently, the authorities closed down the New Jersey track and it was never reopened. The grim reality of Newark and the resultant publicity (which compared short-track motordrome racing to barbaric Roman gladiator sports) marked the beginning of the decline for the short (1/4 to 1/3 mile) motordromes, or "murderdromes" as they began to be labeled by the press. Despite Jake DeRosier's tragic accident and the terrible loss of life at Newark, racing on the pine board tracks continued. |

|

|

|

|

|

Webmaster: daniels@statnekov.com |

Page installed: Nov. 15, 1996 Page revised: June 28, 2003 |