by Daniel K. Statnekov |

| ©1998 - 2006 Daniel K. Statnekov |

For 1916, Ray Creviston was Indian's most successful advertisement.

On track after track, Creviston kept the Indian name at the top of the page

in the trade publications. Although he came from a farm in Indiana,

Creviston talked and acted like someone from the New York Bowery -- a tough

kid who had found his niche in life racing motorcycles.

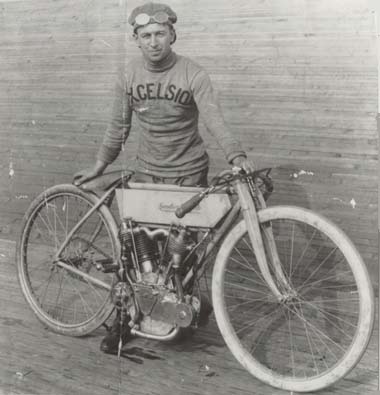

Even Don Johns had to admit that the Springfield company star was extremely skillful, although he didn't like his Indian teammate. Creviston's strategy was to exploit the former Cyclone pilot by riding his pace for lap after lap, waiting for Johns' bike or motor to fail, as it often would. Then Creviston would take the lead to the finish, claiming the prize money for himself. A man riding pace was drafted in the wake of the leading rider with the consequence that the following rider's motor did not have to work as hard as the leader. In addition, the second place rider could execute a maneuver known as "running the pace." The following rider would drop back about ten feet or so, and then blast up the tunnel of low wind resistance left by the front runner. At the last second, just before crashing into the machine ahead of him, the 2nd place rider would swerve aside and pass the leader. Even with a slightly slower machine, the new front runner could hold the lead for a second or two, and if he timed his maneuver precisely, he could stay ahead to the finish. In 1916, it was Bob Perry and Glen Stokes who kept the Excelsior name in the news. Stokes led off by winning a 10-mile National Championship in May, and then he and Perry followed up with a one-two finish at a 100-mile flat track event in June. Schwinn's Big-Valve X had vanquished both Indian's top rider, Ray Creviston, as well as several examples of the new H-D 8-valve. With great anticipation, the entire motorcycle fraternity awaited the final "showdown" at the 3rd running of the Dodge City event. City officials pulled out all the stops for what was being "billed" as the most important race of the year. The streets of the frontier town were decorated with flags and bunting, and a parade was organized to welcome the 30,000 visitors that "streamed" into the city. Several floors of Dodge City's largest hotel, the Harvey House, were reserved as race headquarters. Riders, team managers and their personnel, motorcycle manufacturers, accessory and tire suppliers, along with a legion of sports writers, were all in attendance. Although the smaller races throughout the year were reported by the trade papers and widely followed by an enthusiastic legion of race fans, Harley-Davidson had gained greatly from the reams of publicity generated by winning major events. Consequently, H-D's focused effort in 1916 was to stage a repeat of their previous year's victory at the Dodge City Classic. Ottaway, with the help of Sir Harry Ricardo, had completed the 8-valve cylinder development in time for the 1916 racing season, but it took the first half of the year to perfect the new combustion chamber and multi-valve design. By the time Dodge City came around, Ottaway's riders had logged countless miles (with the half-twin, 4-valve version) on numerous 1/2-mile dirt tracks across the Midwest. With less than two weeks to go before the race, Otto Walker fell while testing one of the new Harley-8's at the Chicago motordrome. Traveling at nearly a hundred miles an hour, Walker's front tire burst in the middle of a turn, throwing the H-D team captain down on the rough boards where he picked up a mass of horrendous splinters. Walker's injuries were serious and he was forced to remain in the hospital for several months. As Harley-Davidson's competition manager, Ottaway had done more than just prepare a fast motorcycle for the July race. The Harley crew chief instituted a rigorous physical training program and drilled his men in team tactics, practiced pit stops with the accompanying factory mechanics, and perfected the flag signaling system that had already paid off in dividends. But with 300 miles at full throttle in the hot summer sun ahead of each rider, it was still anyone's race.

Predictably, Don Johns jumped ahead at the start. By the second

lap, Floyd Clymer, a new member of the H-D team, overhauled and passed

the popular leader. Clymer (who would later become famous as a

publisher of motor-sport magazines) set a furious pace on one of the new

Harley-8's with Bob Perry on a fast Big-Valve Excelsior just behind.

Riding more cautiously to preserve his machine, Johns followed in 3rd place.

On the 5th lap, Perry dropped out with a broken valve. Clymer now widened

his lead when Johns' Indian developed a slipping sprocket which required him

to make a pit stop for an adjustment.

Then, Irving Janke, a H-D factory employee from Milwaukee, received a signal to move up from his position at the rear of the pack. Floyd Clymer, the 21 year-old Harley-Davidson dealer from Denver, stayed out in front, pulling the 19 year-old Janke along in his slip stream. At the 100-mile mark, the Colorado motorcycle dealer had set a new track record for that distance. Shortly thereafter, Janke, having received another signal from the pits, pulled ahead of Clymer who stopped to refuel.

After his pit stop, Clymer resumed the race, reclaiming the lead when

Janke stopped for fuel. Clymer then suffered a flat tire.

Quickly replaced by Ottaway's highly-trained pit crew, he went out

again, caught Janke and battled mile after mile for the lead.

At the 150th mile, the timekeeper announced that the two rider's elapsed

times were identical.

Don Johns' sprocket problems had taken him out of contention, but he still battled with the leaders until about the 200th mile when his motor finally failed. With the famous Indian rider out, Janke and Clymer pulled far ahead of the pack. In the lead, with only 2 laps to go, Clymer's motor broke a valve, relegating him to the sidelines as well.

At the finish, Irving Janke, who had also been riding one of the new

Harley-8's, received the checkered flag two minutes ahead of Excelsior's

Joe Wolters, and more than a half-hour ahead of the nearest Indian.

Although Wolters Big-Valve X turned a time that was nearly 8 minutes

faster than Otto Walker's winning time for the previous year's race,

it was evident that in the 1916 race for technical superiority,

Ottaway's new design had vanquished the competition.

On July 25th, the H-D team reiterated their advantage by claiming the first four places in the race held for professionals at the newly opened Sheepshead Bay board track in Brooklyn, New York. In spite of a pit stop to fix a flat tire, the winner, Leslie "Red" Parkhurst completed the race at a speed in excess of 89 mph. In a follow up 2-mile National Championship over the same course, a three man Harley team swept the boards at speeds of over 90 mph. It was the same throughout the country, the Ottaway-led team winning 15 National Championships for the year. |

|

|

|

|

|

Webmaster: daniels@statnekov.com |

Page installed: Nov. 15, 1996 Page revised: June 28, 2003 |