by Daniel K. Statnekov |

| ©1998 - 2006 Daniel K. Statnekov |

|

In the beginning, motorcycle racing was a competition between the men who

built the first spindly, motor-driven bicycles. As they turned their inventions into

a business, and then into an industry, the manufacturers' continued their "race"

for technical superiority and market share. Competition was the proving ground

for innovation. Star riders emerged along with an enthusiastic riding public.

This is the story of the innovators and the riders, of the engineers and the race

fans; above all, this is the story of the men who gave us the foundation for what

we ride today.

In 1876, the high-wheel bicycle was brought to America and exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. A few of the British-made high-wheelers were imported, and within a short time people were riding them on the streets of Boston. At first, only the affluent could afford the expensive mechanical device, and they were considered a novelty rather than a practical means of transportation. Even when riders were proficient, the often muddy and deeply rutted dirt roads of the time made it a difficult challenge just to stay on board the precarious contrivance. In the 1880's, however, bicycles with equal-sized wheels (called "safety" bicycles) were introduced, and quality machines became more affordable. The "safety" bicycle was not only safer, but easier to ride, and both men and women were drawn to the new invention. For the first time, large numbers of young people had the means to travel beyond their own neighborhoods. By the 1890's, the modern two-wheeler had had a profound effect on American society. As the 20th century approached, the internal combustion engine also came to America from abroad. It didn't take long before mechanically adept young men became impassioned with the idea that the European invention might be used to power wheeled vehicles. Attaching a motor to a bicycle was a natural progression for many of the bicycle builders, and within a short time a variety of motorized two-wheelers were competing for brand-name recognition.

One of the first to enter the business was a Waltham, Massachusetts

company which produced a popular brand of bicycle called the "Orient."

Charles H. Metz, president and inventive genius of the Waltham enterprise, began

his experiments in 1898, concocting a motorized tandem for the purpose of

pacing his team of bicycle racers. Encouraged to increase their speed by

the motorized "training machine," the Orient team was successful, and company

sales increased accordingly.

The industrialist's success with the tandem inspired him to assemble a self-propelled vehicle that could be sold to the public. Beginning with tricycles and quadracycles, Metz eventually constructed a heavy-duty bicycle powered by a De Dion-Bouton engine manufactured in France. The motor-driven Orient was unwieldy, but by early 1900 several prototypes had been built and tested. On July 31, 1900, Metz showcased his invention at the Charles River Race Park in Boston. This public debut of a motor-driven Orient became the first officially recorded motorcycle speed contest in the United States. Albert Champion (a famous rider from France who had been brought to the United States by Metz to promote his line of bicycles) rode 5 miles in a little more than 7 minutes. Shortly thereafter, the motorized Orient was put into production, and in less than a year men were riding them in major cities across the country.

In May of 1901, the first organized motorcycle race in the west took place on

a 1-mile horse racing track in Los Angeles. Ralph Hamlin and his Orient

bested three other riders to win the 10-mile contest in 18 and 1/2 minutes.

By 1902, officially sanctioned endurance competitions were held, and in May of

that same year, the first road race in the United States took place between

Irvington and Milburn, New Jersey (a distance of ten miles). Again,

an Orient was the winner, achieving an average speed of 31 mph.

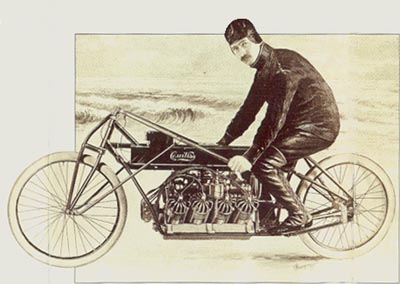

Meanwhile the Waltham company decided to concentrate their efforts on producing a "horseless carriage," and in the Spring of 1902 Charles Metz left the firm to design and manufacture his own motorcycle. Metz's friend and employee, Albert Champion, went on to develop an improved spark plug and founded the spark plug company that still bears his name. The large bicycle manufacturers were not alone in the race to build and market a motor-powered two-wheeler. From a myriad of little workshops that dotted the American landscape other motorized bicycles emerged. The ingenious proprietor of one such shop in upstate New York was Glenn H. Curtiss. Curtiss had been educated in the public schools of his home town, and was notably modest, but from the very beginning his machines were exceptional. In September of 1902, the 24 year-old Curtiss entered the record books for the first time when one of his machines made the fastest time at a Labor Day road race in New York. The following year, the engine builder (who was also a rider) won the first American hillclimb. Soon afterward, Curtiss startled observers in Providence, Rhode Island when he set a record for single cylinder machines by making a 1-mile run at 63.8 mph.

In 1904, Curtiss took one of his machines to Ormond Beach, Florida where he

set a record for 10 miles on the hard-packed sand, and achieved a speed

of 67.3 mph. The following year the innovative designer set yet

another record by riding a twin cylinder Curtiss around the 1-mile dirt

track at Syracuse in exactly 61 seconds.

The engineer's thirst for speed was finally quenched in January of 1907 when he piloted a motorcycle powered by an experimental V-8 motor over a 1-mile beach course in 26 and 2/5th seconds, achieving the astounding speed of 136.3 mph! Before Curtiss was able to make an "officially" timed corroborating run, however, his machine was seriously damaged when a universal joint broke while he was traveling at 90 mph. Lucky to escape injury from the flailing drive shaft, the daring, 28 year-old inventor was forced to call it a day.

Nevertheless, the February, 1907 issue of Scientific American published

an account of the New York motor builder's exploits, and Curtiss was

widely acclaimed for his extraordinary performance. Although Glenn H.

Curtiss would later achieve great fame and fortune (as a pioneer aircraft

designer), those 26 and 2/5th seconds through which he "galloped" a mile

would establish his fame forever. |

|

|

|

|

|

Webmaster: daniels@statnekov.com |

Page installed: Nov. 15, 1996 Page revised: June 28, 2003 |